Seasonal focus

Since taking up his position, François-Xavier Roth’s concerts have undertaken an intense exploration of the history of the Gürzenich Orchestra and the history of music in the Rhineland. The Gürzenich Orchestra looks back upon almost two hundred years of continuous collaboration with preeminent composers. During past seasons, the focus has been on artist personalities of the 20th century, as well as special attention on Johannes Brahms, Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann and Hector Berlioz. Especially the turn of the 19th into the 20th century and the early 20th century brought several fascinating encounters between the Gürzenich Orchestra and great creators of the times: Richard Strauss, Max Reger, Gustav Mahler, Erich Wolfgang Korngold – and not least Béla Bartók. The world premiere of his ballet »The Miraculous Mandarin« at the Cologne Opera made music history, not least because of the scandal the performance caused – due to the libretto which was deemed offensive. Béla Bartók’s music is fascinating for various reasons. It unites the artistic exploration of his own roots – in folk music – and advanced composition techniques.

On the quiet, Béla Bartók also spearheads a little “Hungarian” focus during the 2020/21 season: apart from Bartók, we also celebrate the first guest concert of the great Hungarian conductor and composer Peter Eötvös, the 95th birthday of György Kurtág, and we look forward to a world premiere by Marton Illès, one of the most fascinating composers of the younger generation. However, this focus is not about celebrating a national idiom, but the phenomenon of what fascinating new things may emerge from cultural melting pots.

concerts

Bartók in Cologne

An Essay by Michael Struck-Schloen

»Cologne, the city of churches, monasteries and chapels, whose praises Heinrich Heine sang, has now experienced its first great opera scandal.« As if he had not believed it possible of the bourgeois righteousness of Catholic Cologne, the music critic Hermann Unger – still a friend of musical modernism at the time – reported on tumultuous scenes at the Cologne Opera House on Habsburgerring. Tempers ran high, »minutes of hissing, whistling, foot-stomping, cries of boo which care not for the composer’s presence, even after the ›Iron‹ [Curtain] came down, and when the author and conductor stepped outside the small door, the noise grew into howling – for us, this is quite something.«

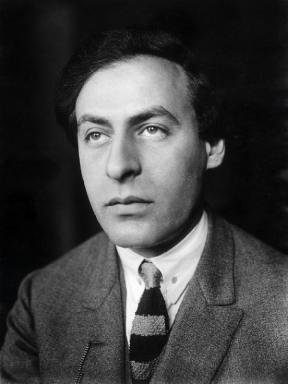

The »author and conductor« were the composer Béla Bartók and his Hungarian friend Eugen (Jenő) Szenkar, chief conductor of the Cologne Opera since 1924. And the work that was so vehemently rejected here was Bartók’s Der wunderbare Mandarin (The Miraculous Mandarin), a tale half-danced and half-mimed, rather unceremoniously drawing the champagne-swilling audience of its world premiere on November 27, 1926 into the morass of a modern metropolis. A girl is forced into prostitution by three »thugs«, read: pimps. Business is bad until a rich Chinese, the sinister »Mandarin«, shows up and falls in love with the girl. The Mandarin is robbed, three brutal attempts are made on his life, but he is only able to die when the young woman begins to love him.

Menyhért Lengyel, the Hungarian journalist, writer and future scriptwriter for Ernst Lubitsch (Ninotchka), had thought up the sociocritical story of a society dominated by violence, which knows love only as a commodity – while the deadly »redemption« of the Mandarin at the end definitely has a strong Christian resonance. No wonder that especially during World War I, Béla Bartók was enthusiastic about Lengyel’s tale. Even the very beginning of his composition with its wild violin runs overlayered with chords in the winds and signals from the trombones – like the noise of human masses and car horns carried towards the listener on the wind, building up to a massive sonic eruption – is reminiscent of Igor Stravinsky’s scandalous work of 1913, Le Sacre du printemps. However, Bartók’s work on The Miraculous Mandarin was interrupted by the composer’s joining of the Hungarian soviet republic of Béla Kún, in which he worked as a music pedagogue, so that the work was only completed shortly before its premiere in Cologne. Opera houses in Budapest, Vienna and Munich had rejected the piece because of its controversial content, perhaps also because of the enormous number of musical rehearsals required; ultimately only Eugen Szenkar was willing to run the risk of giving its world premiere. As chief conductor of the opera in Frankfurt am Main, he had already given the German premieres of Bartók’s dance piece The Wooden Prince and his only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle (Bluebeard also opened the Cologne performance premiering the Mandarin).

Adenauer Intervenes

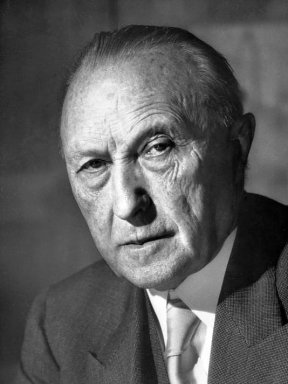

Man weiß, wie das Kölner Abenteuer endete. Nicht nur das Publikum, sondern auch die Presse echauffierte sich über Inhalt und Musik, die im Kölner Stadtanzeiger schon mit aggressiv-rassistischem Unterton als » Hottentottenkralsmusik « abgefertigt wurde, » die uns Bartók als die Ausgeburt eines entarteten Musiksinns bescherte. « Oberbürgermeister Konrad Adenauer war durch den Skandal und die konservativen Proteste so alarmiert, dass er Szenkar in sein Büro zitierte. » Dr. Adenauer machte mir die bittersten Vorwürfe, wie es mir eingefallen wäre, so ein Schmutzwerk aufzuführen, und forderte die sofortige Absetzung des Werkes! Ich versuchte ihn von seinem Irrtum zu überzeugen, Bartók wäre unser größter zeitgenössischer Komponist, man möge sich nicht vor der musikalischen Welt lächerlich machen! Doch er verharrte auf seinem Standpunkt. « Tatsächlich wurde die Produktion abgesetzt – eine gutsherrenhafte Entscheidung, die überregional heiß diskutiert wurde und Bartóks Werk nachhaltig schadete. Bis zum Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs gab es nur zwei weitere Bühnenproduktionen des Wunderbaren Mandarin in Prag ( 1927 ) und in Mailand ( 1942 ), wo das faschistische Regime von dem Stück offenbar weniger ideologische Sprengkraft befürchtete als die Deutschen. Um wenigstens die Musik zu retten, hat Bartók eine Konzertsuite arrangiert, die heute zum festen Bestand im Orchesterrepertoire der frühen Moderne gehört. Für die Bühne hat er nach dem »Wunderbaren Mandarin« nie wieder komponiert.

It is worth noting that Bartók’s appearance in Cologne at the time was by no means a modernist »accident« in the concert and opera life of the Cathedral City – on the contrary. Just as Szenkar presented novelties at the opera, including Sergei Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges or two operas by the Schoenberg student Egon Wellesz, the city’s general music director Hermann Abendroth had been adding a steady diet of contemporary music to the concerts of the Gürzenich Orchestra since the mid-1920s. The conservatives – Richard Strauss, Hans Pfitzner, Walter Braunfels, Ewald Straesser or Paul Graener – were equally represented in the repertoire as the »avant-gardists« Paul Hindemith, Arthur Honegger, Ernst Křenek, Igor Stravinsky – and of course Béla Bartók, who nonetheless only returned once to Cologne after the debacle of the Mandarin. In March 1928, he performed the solo part of his Piano Concerto No. 1, which seemed hardly less unwieldy than the scandalous stage work, given its harsh soundscape redolent of New Objectivity. Afterwards, no Bartók work was included in the programmes of Cologne’s municipal orchestra – in stark contrast to other major German cities, where Bartók was heard regularly until 1933, and even thereafter in some places. Even the National Socialists did not generally ban Bartók’s works initially – although they disapproved of the fact that the composer protested against the authoritarian paternalism in artistic matters now prevalent in Germany or his native Hungary.

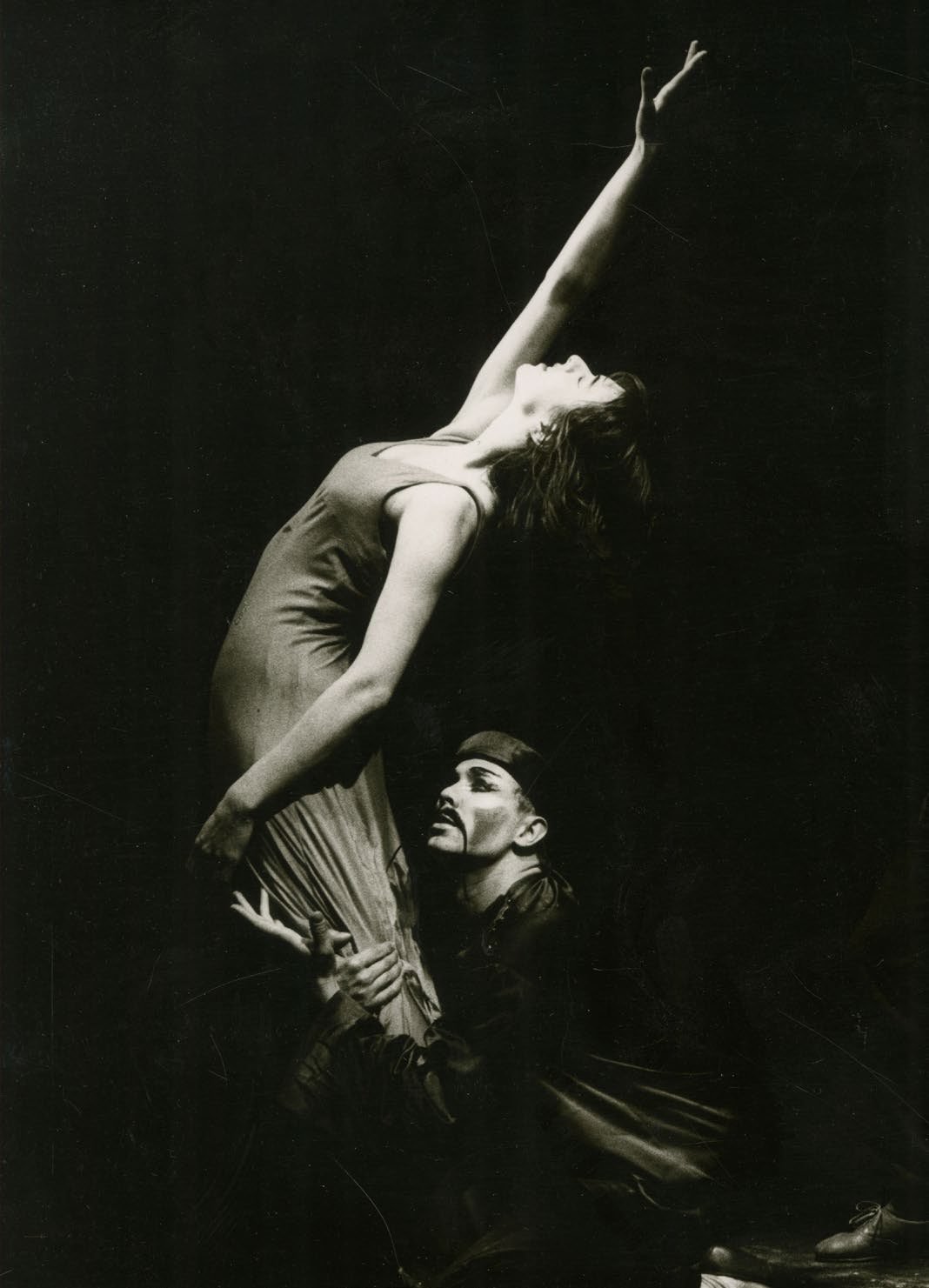

Pusillanimous Rehabilitation

After World War II, the new Gürzenich-Kapellmeister Günter Wand restored modernist music, ostracized for twelve years, to the orchestra’s programmes. His personal favourites were Hindemith, Stravinsky, Bernd Alois Zimmermann and the former director of the Cologne Music Academy, Walter Braunfels. Günter Wand was somewhat less decisive in propagating the late works of Béla Bartók, who had died in New York in 1945; he did, however, at least secure the German premiere of Bartók’s Violin Concerto No. 2 with Günter Kehr as the soloist for 1947. Over the course of the years, this was followed by the Cologne premieres of the Viola Concerto’s posthumous reconstruction (1950, with William Primrose as the soloist), the Concerto for Orchestra (1954) – which immediately became an effective favourite in the Gürzenich Orchestra’s repertoire –, the Divertimento and the Music for String Instruments, Percussion and Celesta (both 1955). Relatively late did the Gürzenich witness the revival of the music of The Miraculous Mandarin: a very young James Conlon conducted the concert suite there in November 1975. However, the Cologne audience had already had an opportunity a few years earlier to revise its harsh 1926 judgment of the ballet-pantomime. In 1960, Aurel von Milloss had been appointed head of dance at the newly-built Opera House on Offenbachplatz, the first of international standing to hold this position; the photographer Chargesheimer captured Milloss’ rehearsals with prima ballerina Tilly Söffing in dynamic images. Chargesheimer was also the scenographer for a ballet evening in September 1961 which featured not only pieces by Stravinsky and Prokofiev, but also a first revival of The Miraculous Mandarin – Milloss had already staged it in Fascist Italy in 1942 and had remained an resolute champion of the work. Dance experienced a second heyday in Cologne since the 1970s, when Jochen Ulrich’s Tanzforum was established; it was Ulrich who created an impressive choreography for The Miraculous Mandarin for an all-Bartók evening in 1980, featuring the fabulous Ralf Harster in the title role. No one in the audience batted an eyelash at the expressionist music which had long attained the status of a modern classic, given the post-1945 musical avant-garde. The time seemed ripe for a rehabilitation of the piece. This was also proven by a 1985 book by dance historian Annette von Wangenheim, the first to recount the »Passion« of Bartók’s Mandarin in Cologne, with the help of numerous documents. Reading them, one can marvel at the confluence of audience wrath, populist battles in the press, and spineless cultural politics which cared little for the freedom of art. Especially today, the fate of Bartók’s Miraculous Mandarin should remind us all of the risks inherent in letting music falling prey to the unholy machinations of politics.

Experience Bartók